For nearly 100 years, the history of the farm bill largely tracks the history of food production in the United States as the legislation has evolved to meet the needs of farmers and consumers alike. Agriculture’s role in providing food security, and in turn national security, to the United States is more important than ever. And now, work on the next farm bill continues during a period of volatility on every front – political, economic, environmental and beyond.

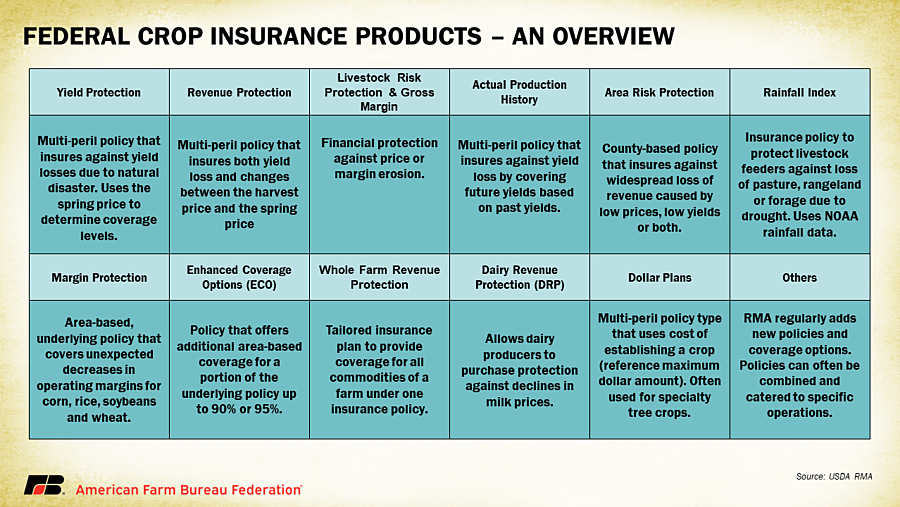

Crop insurance is exactly like it sounds: an insurance product designed to help shield farmers against a myriad of potential risks, ranging from adverse growing conditions to market fluctuations. This coverage fills crucial gaps that private insurance products may neglect or find impossible to address alone. Supported by the federal government, these policies provide financial stability for farmers, who can tailor coverage to suit their unique operational needs from a variety of policy options. Products are available for annual crops, perennial tree crops and livestock and may protect against the value of the commodity, the replacement value of a damaged or destroyed commodity, or the operating margin for a commodity.

Background & Funding

Crop insurance has its roots as part of the policy response to the Great Depression and was permanently authorized under the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 and the Federal Crop Insurance Act of 1980. The Federal Crop Insurance Corporation is the agency that finances the program’s functions through mandatory appropriations of “sums as necessary.” The Risk Management Agency (RMA) has discretion over policy offerings, coverage and administration. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects net spending each year and estimates the costs of supporting a portion of a farmers’ policy premium, compensating private insurers for their administrative and operating expenses and reinsuring losses from policies sold (transferring all or part of the risk to another insurer). Projections depend partly on commodity prices. If commodity prices increase in the future, the expected value of insured crops would rise, leading to higher anticipated values for insured liability and premium discounts compared to scenarios with lower commodity prices. For marketing year 2024, the CBO projects a total program cost of $12.37 billion.

Title XI of the farm bill supports new and continued insurance products farmers may purchase through a public-private partnership. Private-sector companies known as approved insurance providers (AIPs) sell and service crop insurance policies while USDA plays critical roles in financing, regulating and reinsuring the policies. This model is essential to service farmers and ranchers and the uniqueness of each of their operations across the country as AIPs provide the boots-on-the-ground service and processing, relieving USDA of administrative burdens. Farmers work with their local crop insurance agent to select the base coverage policy that fits their farm or ranch. Additional products, or endorsements (similar to options for automobile or home insurance products), can be added to underlying policies for additional costs.

Covered Perils

Crop insurance provides protection for a limited number of events or conditions. These are called “covered perils” or “causes of loss” and include adverse weather conditions (e.g., hail, frost, drought, flooding); failure of irrigation water supply (if caused by an insured peril during the period of insurance coverage); fire (due to natural causes); plant diseases (provided the farmer followed guidance on proper application of disease control measures); and insect and wildlife damage (provided the farmer followed guidance on proper application of pest and wildlife control measures). Certain policies also insure against losses from market price declines. Crop insurance does not cover damage or loss of production due to the inability to market a crop for any reason other than actual physical damage for an insurable cause of loss.

Selecting a Crop Insurance Product

Farmers have the flexibility to customize their crop insurance to align with their farm management objectives and practices. In many cases farmers can choose to insure based on a farm’s average yield, its average crop revenue, the county’s average yield or the county’s average revenue. Revenue protection is usually more expensive due to the higher level of risk associated with market fluctuations. Using farm-level averages is also more expensive than using county options because of the smaller risk pool.

To begin, farmers must first select the level of coverage they want to purchase. The coverage level refers to the percentage of commodity value that is covered — referred to as the liability — and the corresponding loss that a farmer must incur before an indemnity payment will be made (comparable to a deductible for home or auto insurance). A coverage level of 80%, for example, would insure losses greater than 20% of the liability but provide no protection for losses less than 20% of the liability. The lower the coverage level, the more extreme the losses have to be to trigger an indemnity, which lowers the associated risk of a plan. For this reason, farmers pay a higher cost for higher coverage levels.

A CAT plan, known as catastrophic coverage, represents the minimum available coverage level and only makes indemnity payments (payouts from a triggered crop insurance plan) when a farmer loses 50% or more of their expected yields.

Farmers participating in crop insurance are required to follow USDA’s guidance on good farm practices while planting, growing and harvesting their crops. This reduces risk to the program related to operator-caused crop losses. These practices vary by area but can include actions taken before planting (properly preparing a field), during the growth period (properly watering crops) and during harvest (following harvesting procedures that minimize crop losses). Failure to comply with these practices can disqualify a farmer from crop insurance. Certain operation characteristics (such as whether acreage is irrigated or not) can change the level of risk exposure farmers have regarding good farm practices and with it the cost of a policy.

Federal crop insurance adjusts for differences in land and crop ownership through five types of insured units: basic, optional, enterprise, multicounty enterprise and whole farm. As noted by the Congressional Research Service, basic units are all the insurable acreage in a county that’s either owned or cash rented and planted to one crop. Optional units subdivide a basic unit by geographic boundaries and allow farmers to tailor their crop insurance coverage for differences in growing conditions within the basic unit. Enterprise units include all the insurable acreage for a crop in a county, regardless of whether the land is owned or rented by the farm operator. Multicounty enterprise units are enterprise units that include all the insurable acreage in two contiguous counties. Lastly, whole farm units must include all crops grown and all land insured for the farm, regardless of county boundaries.

Premium Support

USDA’s administrative burdens for the program are reduced by providing payments to AIPs to distribute, rather than the agency directly working with hundreds of thousands of crop insurance policy holders. AIPs receive payments from USDA on behalf of farmers to offset a portion of premium costs. For most acreage policies discount rates (the portion of a crop insurance premium paid for by the government) are set by statute set in the farm bill and may vary based on the coverage level a farmer selects. USDA pays 100% of the premium rate for CAT coverage levels at 50% coverage, then the levels of support decrease as selected coverage levels increase (table 1). Beginning and veteran farmers are entitled to a 10% discount rate above the amounts listed.

In addition to premiums, farmers also pay administrative fees. For CAT coverage, farmers pay $655 per crop per county with no discount. For policies with higher coverage levels, the administrative fee is $30 per crop per county in addition to the farmer-paid premium.

Crop insurance policies are priced in a way that must be “actuarily fair” and USDA is statutorily required to operate in ways that “improve the actuarial soundness of federal multiperil crop insurance coverage.” This means the total value of premiums paid over many years should be about equal to the value of indemnity payments distributed. One way USDA measures success is through a financial performance indicator known as a loss ratio defined as the indemnities paid divided by the premiums collected for policies in a given year. A loss ratio of one means indemnities equaled premiums, while a loss ratio greater than one means indemnities were higher than premiums and the opposite for a loss ratio lower than one. As of March 2024, the loss ratio for 2023 policies is 0.86, meaning that more premiums were paid for policies than indemnities paid for losses incurred.

Creating New Insurance Policies

The Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC) board of directors manages the federal crop insurance program and must approve new crop insurance policies and can do so through a process known as 508(h) submissions. New policies can be submitted by RMA or from nongovernment actors including AIPs, colleges and universities, cooperatives, trade associations and even individuals. External experts review concept proposals and full 508(h) submissions prior to consideration for adoption by the FCIC board of directors. When considering new 508(h) proposals, the FCIC board of directors must consider the interests of agricultural producers and the potential for “significant adverse impact on the crop insurance delivery system” (i.e., keeping crop insurance actuarially sound). The 508(h) proposal must also provide coverage that is likely to be “viable and marketable,” address “a clear and identifiable flaw or problem in an existing policy,” or provide coverage for a commodity that either could not be covered or had low participation under the existing coverage. Costs of preparing 508(h) proposals can be reimbursed by USDA if the FCIC board of directors adopts the proposal, incentivizing thoughtful and innovative submissions. From 2000 to 2023 the number of policies sold has increased from 1.94 million to 2.34 million.

Conservation Compliance Requirements

To encourage the conservation of wetlands and highly erodible lands, the Federal Crop Insurance Program requires participants to meet conservation compliance requirements. To comply, farmers must agree to maintain a minimum level of conservation on highly erodible lands and not convert wetlands to crop production. The 2014 farm bill included a provision that could eliminate crop insurance support for producers who are out of compliance with conservation requirements. The 2018 farm bill introduced new specifications that qualified certain voluntary uses of cover crops as a type of good farming practice – allowing land planted with cover crops to maintain crop insurance eligibility. Cutoff dates that applied to prevent plant acres in 2019 and 2020 were also adjusted as they may have deterred farmers from applying cover crops to prevent plant acres.

Summary

Crop insurance remains a crucial safeguard for farmers, tracing back to the Great Depression and evolving into a vital tool amidst today's market and weather volatility. Supported by a partnership among the federal government, private insurers and farmers, it offers tailored protection against diverse risks for farmers across the nation. Farmers bear a significant part of the cost themselves, and ongoing innovation in policy offerings allows more and more farmers to shield themselves from unexpected losses, bolstering the resiliency of the food system. Provisions that keep program costs in check and promote good farm practices optimize the return on investment for taxpayers. As the U.S. navigates an increasingly uncertain future, improving crop insurance through passage of a new five-year farm bill is essential for safeguarding the livelihoods of farmers, the stability of rural economies and the reliability of our food system.